Benshi 弁士

Japanese performers who provided live narration for silent films

Seanchaí

Traditional Irish storyteller/historian, a bearer of "old lore"

It all started by chance. A brief conversation with a stranger on a train from Tokyo to Kyoto. She told me about Benshi performers. I had never heard of them before and was intrigued. On her recommendation I went to see some performances in a small intimate space that evening. It was a double bill, the first part a 1950’s Godzilla/Disaster B Movie involved a young man speaking rapidly surrounded by a tiny model city laid out with cardboard buildings and model cars directly in front of the screen. As the monster on film destroyed the city, the Benshi likewise crushed his model. My inner set designer was horrified! It was great physical comedy, good fun but the emphasis was very much on the performer and the film took second place.

However the second part was extraordinary. The Benshi, an older man sat on an empty stage. Behind him a silent black and white Samurai film was showing. His script was minimal and spare, his voice deep and resonant. I later found out that the plot involved a feud between two factions and the Benshi was introducing the characters and sketching some background detail of their involvement in the feud. The effect was mesmeric. The live performer and the silent film co-existed beautifully.

Some months later back in Dublin I was still haunted by this piece. I had been given a slot in Project Brand New, a wonderful initiative that allows for ideas for performance to be road tested in front of a live audience. I was working with performance artist Amanda Coogan to see if we could replicate the Benshi experience. One day during rehearsal while trying to explain my Japanese experience with the samurai film I suggested that it would be like taking a film such as Man of Aran and having Liam Ó Maonlaí narrate it. Another chance comment and a seed sown.

I bought the DVD a few days later and was disappointed. I had forgotten about the heavily orchestrated soundtrack and the clumsily recorded dialogue. It was only when I watched it with the sound turned down that I began to see it’s real potential.

I contacted Síle Nic Chonaonaigh, initially to see what she thought about the idea and to ask her if she would come on board to write the script. I had worked with Maura O’Keefe and once off productions before and I was delighted when she agreed to produce. Mel Mercier was my first choice as composer and he needed little persuading. He suggested Chris Shutt as sound designer and the team was almost in place. Last but not least Liam agreed to take it on and the dream team was complete. I have been blessed to get my first choice of collaborators to embark on this journey with me. My only regret is that I never got the Japanese woman’s name or contact details so I could express my gratitude to her too.

However the second part was extraordinary. The Benshi, an older man sat on an empty stage. Behind him a silent black and white Samurai film was showing. His script was minimal and spare, his voice deep and resonant. I later found out that the plot involved a feud between two factions and the Benshi was introducing the characters and sketching some background detail of their involvement in the feud. The effect was mesmeric. The live performer and the silent film co-existed beautifully.

Some months later back in Dublin I was still haunted by this piece. I had been given a slot in Project Brand New, a wonderful initiative that allows for ideas for performance to be road tested in front of a live audience. I was working with performance artist Amanda Coogan to see if we could replicate the Benshi experience. One day during rehearsal while trying to explain my Japanese experience with the samurai film I suggested that it would be like taking a film such as Man of Aran and having Liam Ó Maonlaí narrate it. Another chance comment and a seed sown.

I bought the DVD a few days later and was disappointed. I had forgotten about the heavily orchestrated soundtrack and the clumsily recorded dialogue. It was only when I watched it with the sound turned down that I began to see it’s real potential.

I contacted Síle Nic Chonaonaigh, initially to see what she thought about the idea and to ask her if she would come on board to write the script. I had worked with Maura O’Keefe and once off productions before and I was delighted when she agreed to produce. Mel Mercier was my first choice as composer and he needed little persuading. He suggested Chris Shutt as sound designer and the team was almost in place. Last but not least Liam agreed to take it on and the dream team was complete. I have been blessed to get my first choice of collaborators to embark on this journey with me. My only regret is that I never got the Japanese woman’s name or contact details so I could express my gratitude to her too.

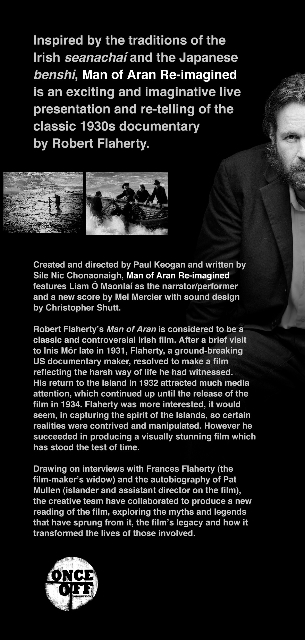

Liam Ó Maonlaí in Man of Aran Re-imagined. Photo Ros Kavanagh

The making of a modern Man of Aran

PETER CRAWLEY

Irish Times Fri, Dec 10, 2010

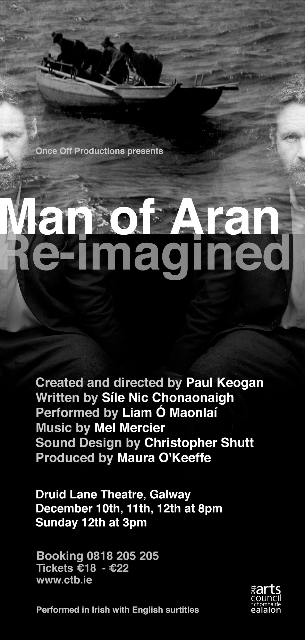

The idea for a reworking of the 1936 film came to Paul Keogan after an encounter on a Tokyo train – but the result remains very Irish.

There are two sides to every story. But how many fictions and realities can share space in a single film sequence? On a bitterly cold day in Galway last week, as the climax of Robert Flaherty’s 1934 movie Man of Aran played overhead, the cast and crew of an intriguing new performance project began to unpick a myth.

Flaherty’s film could never be called a documentary without complication. Centred on one family’s harsh life on rugged Inis Mór, it cast the roles with the island’s most photogenic locals – including Maggie Dirrane as the woman and Coleman “Tiger” King as the man of Aran – and sensationalised each hardship: most notoriously, men hunting a basking shark with a harpoon, a practice that had not been seen for nearly a century.

In Druid Lane Theatre, where Paul Keogan’s Man of Aran Re-Imagined is performing this week, the final scene began to acquire waves of new meaning.

Delivering a text by Síle Nic Chonaonaigh, the performer Liam Ó Maonlaí spoke with sombre cadences over a delicate new score by Mel Mercier and artful sound design from Christopher Shutt. As three men rowed a currach through a roiling sea in the film’s still sharply entrancing print, we heard the recollections of the film’s assistant director, Pat Mullan, an Inis Mór local who was also one of the rowers. Routinely sent back into perilous waters, for take after take, Mullan’s words of grave doubt and cultural deference gave further layers to the visuals. Keogan’s “Re- Imagining” could have demystified the movie. Instead it swelled with greater drama.

This is Paul Keogan’s first professional work as director, a man better known in the theatre and opera as a designer in demand. To glance at his expansive résumé it seems easier to list the productions he has not worked on in a given year, and as a lighting and set designer it’s difficult to pin down his style or his tastes. He speaks with equal enthusiasm about working with different directors; the cinematic references of Jimmy Fay, the clear logical underpinning of Jim Culleton, the physical precision of Selina Cartmell, or the psycho- logical character understanding of Róisín McBrinn.

His one constant, though, is the relish of challenge. When he comments on the arts, its policies, institutions and inherent values, he is both clear-sighted and often fearlessly outspoken. Even as a student of drama in Trinity College, learning about lighting involved overcoming a fear of heights.

Man of Aran Re-Imagined was inspired by an accidental discovery on a train journey between Tokyo and Kyoto a couple of years ago when a fellow passenger told him about Japanese benshi – the live narrators and interpreters of silent films for unfamiliar audiences. Enthused by a later performance, Keogan found himself picking an example at random to explain the phenomenon. “You take a film like Man of Aran ,” he told the performance artist Amanda Coogan, “and you put it together with someone like Liam Ó Maonlaí.” The die was cast.

For the project, produced by Once Off Productions, Keogan is credited as creator and director, positions, he agrees, that counter the responsive nature of a designer. But the production has been a model of collaboration.

Everyone was equally spurred by a disappointment with Flaherty’s original, diplomatically agreeing that its soundtrack, a saccharine nod to diddly-aye, had “not withstood the test of time”.

“How can you look away from the culture and not bring it into the film?” wondered Ó Maonlaí about its ersatz qualities, its erasures and crudely overdubbed English, just as Nic Chonaonaigh acknowledged that her Irish language text had to involve as much comment and critique as character and lyricism. In the years after the film’s making, Tiger King gave this bi-lingual reflection: “Bhí fhios againne go maith gur bullshit a bhí ann.” For all its beauty, does Flaherty’s film strike its new interpreters as a fundamentally dishonest work? “That’s a really tricky question to answer,” said Keogan. “If you look at the DVD as it is with the sound up, you have one experience. If you turn the sound down, you have a completely different one.” Were it not for the deep consideration and painstaking work beneath fitting live performance to a recorded medium, you could see this as an elaborate DVD extra. Keogan doesn’t discourage the association. “That is a reference,” he says, “It’s a live DVD commentary.” It is also the product, he emphasises, of people working outside their comfort zones, bringing a fresh, informed perspective to a problematic classic and seeing something new.

“I’m seeing Liam very much as an actor, with extraordinary musical capabilities, but he’s not a musician here. Síle’s a director who’s being a writer. I’m a lighting designer who’s pretending to direct.” He pauses over Shutt, the witty sound designer who is working on sound design. “Actually Chris,” he says, “you should try harder.”

Man of Aran Re-Imagined runs from until Sunday in Druid Lane Theatre, Galway

© 2010 The Irish Times

PETER CRAWLEY

Irish Times Fri, Dec 10, 2010

The idea for a reworking of the 1936 film came to Paul Keogan after an encounter on a Tokyo train – but the result remains very Irish.

There are two sides to every story. But how many fictions and realities can share space in a single film sequence? On a bitterly cold day in Galway last week, as the climax of Robert Flaherty’s 1934 movie Man of Aran played overhead, the cast and crew of an intriguing new performance project began to unpick a myth.

Flaherty’s film could never be called a documentary without complication. Centred on one family’s harsh life on rugged Inis Mór, it cast the roles with the island’s most photogenic locals – including Maggie Dirrane as the woman and Coleman “Tiger” King as the man of Aran – and sensationalised each hardship: most notoriously, men hunting a basking shark with a harpoon, a practice that had not been seen for nearly a century.

In Druid Lane Theatre, where Paul Keogan’s Man of Aran Re-Imagined is performing this week, the final scene began to acquire waves of new meaning.

Delivering a text by Síle Nic Chonaonaigh, the performer Liam Ó Maonlaí spoke with sombre cadences over a delicate new score by Mel Mercier and artful sound design from Christopher Shutt. As three men rowed a currach through a roiling sea in the film’s still sharply entrancing print, we heard the recollections of the film’s assistant director, Pat Mullan, an Inis Mór local who was also one of the rowers. Routinely sent back into perilous waters, for take after take, Mullan’s words of grave doubt and cultural deference gave further layers to the visuals. Keogan’s “Re- Imagining” could have demystified the movie. Instead it swelled with greater drama.

This is Paul Keogan’s first professional work as director, a man better known in the theatre and opera as a designer in demand. To glance at his expansive résumé it seems easier to list the productions he has not worked on in a given year, and as a lighting and set designer it’s difficult to pin down his style or his tastes. He speaks with equal enthusiasm about working with different directors; the cinematic references of Jimmy Fay, the clear logical underpinning of Jim Culleton, the physical precision of Selina Cartmell, or the psycho- logical character understanding of Róisín McBrinn.

His one constant, though, is the relish of challenge. When he comments on the arts, its policies, institutions and inherent values, he is both clear-sighted and often fearlessly outspoken. Even as a student of drama in Trinity College, learning about lighting involved overcoming a fear of heights.

Man of Aran Re-Imagined was inspired by an accidental discovery on a train journey between Tokyo and Kyoto a couple of years ago when a fellow passenger told him about Japanese benshi – the live narrators and interpreters of silent films for unfamiliar audiences. Enthused by a later performance, Keogan found himself picking an example at random to explain the phenomenon. “You take a film like Man of Aran ,” he told the performance artist Amanda Coogan, “and you put it together with someone like Liam Ó Maonlaí.” The die was cast.

For the project, produced by Once Off Productions, Keogan is credited as creator and director, positions, he agrees, that counter the responsive nature of a designer. But the production has been a model of collaboration.

Everyone was equally spurred by a disappointment with Flaherty’s original, diplomatically agreeing that its soundtrack, a saccharine nod to diddly-aye, had “not withstood the test of time”.

“How can you look away from the culture and not bring it into the film?” wondered Ó Maonlaí about its ersatz qualities, its erasures and crudely overdubbed English, just as Nic Chonaonaigh acknowledged that her Irish language text had to involve as much comment and critique as character and lyricism. In the years after the film’s making, Tiger King gave this bi-lingual reflection: “Bhí fhios againne go maith gur bullshit a bhí ann.” For all its beauty, does Flaherty’s film strike its new interpreters as a fundamentally dishonest work? “That’s a really tricky question to answer,” said Keogan. “If you look at the DVD as it is with the sound up, you have one experience. If you turn the sound down, you have a completely different one.” Were it not for the deep consideration and painstaking work beneath fitting live performance to a recorded medium, you could see this as an elaborate DVD extra. Keogan doesn’t discourage the association. “That is a reference,” he says, “It’s a live DVD commentary.” It is also the product, he emphasises, of people working outside their comfort zones, bringing a fresh, informed perspective to a problematic classic and seeing something new.

“I’m seeing Liam very much as an actor, with extraordinary musical capabilities, but he’s not a musician here. Síle’s a director who’s being a writer. I’m a lighting designer who’s pretending to direct.” He pauses over Shutt, the witty sound designer who is working on sound design. “Actually Chris,” he says, “you should try harder.”

Man of Aran Re-Imagined runs from until Sunday in Druid Lane Theatre, Galway

© 2010 The Irish Times

|

Site Design © Paul Keogan 2023 |